Stop saying that AI is just a tool and it only matters how it is used

I'm tired of this phrase and this simple way of thinking about tools. This blog post is a wandering train of thought on the topic of what tools are and why it matters to be even slightly more mature in how we think about them.

I’ve been thinking constantly about the common and casual phrase I’ve heard so often, “AI is just a tool - it matters how you use it.” This has been the rallying cry of tech-loving academics who no longer do their own research, tech bros who salivate over generative images of criminal depictions of people without their consent, and business-minded folks who actually don’t care about AI but see this as an opportunity to rake in more and more money for themselves.

The phrase is deceptively simple and deceptively misleading. Yes, AI is a tool. And yes, it is important how we choose to use tools.

But the phrase’s core reasoning is insultingly naive. It doesn’t work well for most things: “A car is just a tool, it matters how you drive it.” Well… oil and gas is destroying the climate, seatbelts help save lives whether or not someone is a good driver, and since the invention of cars, American city design has become utterly unwalkable and unlivable.

So there is much more to tools than how we use them. And since I have seen this phrase used by award-winning, highly successful HCI researchers, I can’t help but wonder if some people really just want to shut up folks who disagree with them. Are these academics just afraid their ethics are being interrogated? Or do some people believe so strongly in the benefits of AI that they really don’t care for the downsides? I’m not sure why some cling so feverishly to this childish mantra that “AI is just a tool,” but I certainly lose respect any time I see someone who should know better use it.

Have we not talked about how all artifacts have politics in our discipline for decades and decades? Tools are massively impactful on our environment, law, policy, and what it means to be human. Believing that AI is “just a tool” is naive at best and dismissive at worst because nothing about tools is “just” anything. They are highly complex parts of life and culture.

The last part of the phrase, “it matters how you use it” is also deceptively misleading and overly simplistic. Oh really? The entirety of all ethics involved in modern technological ecosystems and infrastructures rests solely on how a singular person chooses to use something? Individual action won’t solve all of our problems. Some ethical issues are systemic and require more than just one person choosing the right method for using a piece of technology.

The reason people say something like this is because it immediately invites solutionism. “It matters how you use it” is an intellectual half-gesture. The audience who hears that phrase will sagely agree, “ah, of course, in my wisdom I know how to use things well. And this means that is all there is to it!” It turns people into fools, thinking they are wizards. “It matters how you use it” is then a glaringly simple, solveable problem space: well, some people just don’t know. “All we need to do is teach people how to swing a hammer, and then hammers are ethically good!” Nonsense.

Even a hammer, made of wood and iron, requires trees to be cut down and earth to be mined up. A simple hammer requires laws to be written about fair treatment of workers in multiple industries, sustainability of various biological and geological environments, and regulation about the sale and use of the hammer. “It matters how you use it,” in regards to artificial intelligence ignores the reality that it also matters how AI is made, how AI is disseminated, the waste AI produces, the damage AI causes to economies and environments, and the overall impact that AI has on human life and culture.

“It matters how you use it” is something that an immature and self-absorbed young child would say, a child who has yet to reckon with the reality that they live in a society full of other people and other living organisms and participates in a system of entities that are all constantly fighting for fairness, dignity, and survival.

I loathe the phrase, “AI is just a tool, it matters how you use it.”

On tools and being

And tools use us by their design. This is Heidegger’s Gestell (“en-framing”): the notion that technologies shape who we are because of their design and use. A hammer isn’t just made of wood and iron, then. A hammer is a hammer because of what it does and who we become when we use it.

Tools, then, aren’t “neutral” in any way.

My dissertation centers on this tension and builds on it: well, if tools aren’t neutral - then what? In my thesis, I focus on the accessibility of visualizations, with tool design as an intervention. But the concepts, imperatives, and calls to action in my dissertation can be applied more broadly:

We must interrogate and reshape our technologies. We need to fight back against design that flattens our humanity at the benefit of efficiency and productivity. We need to question how our tools have created infrastructures and landscapes that are hostile to human existence. And of course:

We must interrogate how tools shape us, by their design.

Take the “chair:”

Anna Gyllenklev writes, “Ever feel like your chair is bossing you around? “Sit still. Face forward. Behave.”

A chair orders you to sit and sit in a particular way, by its design.

Your being is intended through the tool: you are intended to sit still, face forward, and behave. Artificial intelligence works in exactly the same way. We might use these tools believing that “it’s all in how you use them” - and yet, still, our tools are using us. Our being is, perhaps more now than it has ever been, intended to become reliant on our tooling. All tools do this, it isn’t new.

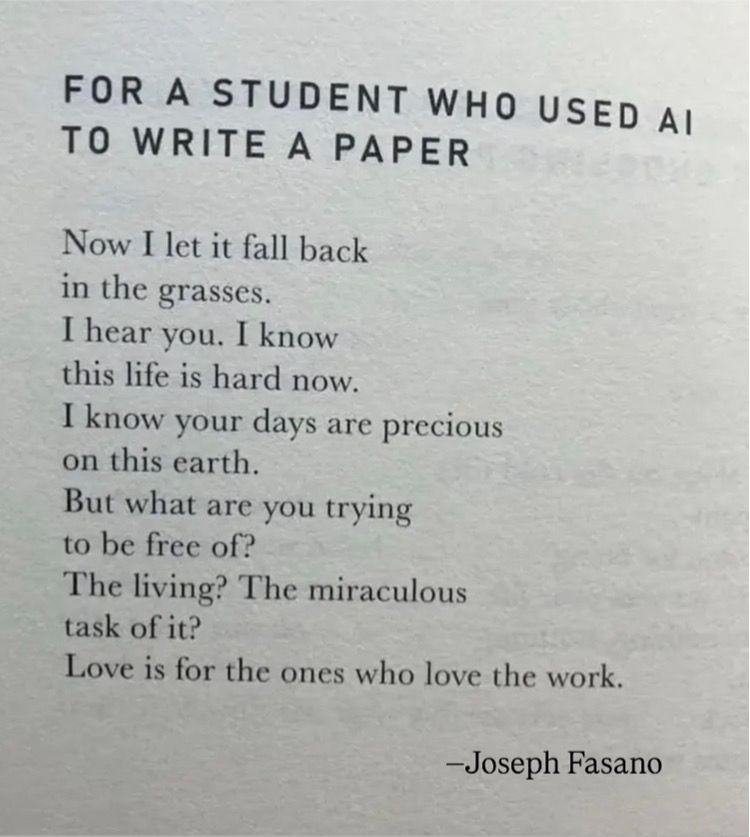

But artificial intelligence, far more than any tool we’ve ever created, intends us not just to sit forward and behave, but to cease to think critically, to cease to imagine, and, most temptingly, to cease to feel struggle and pain.

Knowing the difference between drudgery and meaningful struggle

The greatest selling point of automation has always been to remove drudgery. And at the heart of drudgery is a certain variety of struggle and pain.

Artificial intelligence in our modern imagination and material reality is sold to consumers as a solution to all struggle: we can simply ask for art and it materializes before us. There is no struggle at all involved, thus the terrible labor of being an artist is removed!

But is all struggle the same thing as drudgery?

And AI is not new, in this regard. The flattening of all pains into a total loss of pain has previously been the job of recreational drug use or theology. So AI is therefore more like an opiate than anything else. Or perhaps, given the fervor of its modern supplicants, it is more like a religion on drugs.

Modern automation of everything, including art, thinking, and writing, numbs who we are. Total automation softens our ability to discern between struggle that makes and pain that takes.

How you answer these two questions should inform how you treat the use of AI:

If it was possible: Should we climb a mountain, or flatten it? And should we climb a curb, or cut it?

Climbing a mountain is the point: the struggle and overcoming it is what matters. But a curb? A curb is a barrier to access. The struggle against a curb shouldn’t exist. This is why, in accessibility, we try to cut curbs and flatten barriers whenever we can.

Take the gym, for example: struggle against the pain of exercise is rewarding and uplifting. The weights don’t have to be moved, lifting them isn’t a required task of us. It would be nonsense to ask a robot to lift weights for us at the gym.

However, tools and technologies that improve how we lift weights are a recognition of our love of lifting. Newer, safer weight lifting machines, protections from dropped weights, stronger cables, mirrors in front of the dumbells, and so on. Many technologies exist to enhance our human love of struggle.

But we cease to feel struggle when we use AI. We don’t need to write our mothers a well-meaning email on her birthday, we don’t need to make the case for our promotion to our bosses, we don’t need to think through the hard parts of an algorithm we are writing, and, when it comes to art, we don’t need to feel the pain of improving our craft. We simply prompt, and (optionally) we could choose to do the work of validating whatever it came up with. But of course, automating validation is just another thing that modern AI-dreamers dream of.

Artificial intelligence is the quintessential tool-as-a-drug. It operates with an economy of infinity, as if there is no downside to any interaction and no risk or cost involved in anything we do.

But the greatest cost comes in how our tooling shapes us and “flattens our being” (as Heidegger writes). This is because truly feeling and experiencing pain and struggle is central to our humanity. We are both unique individuals and collectively unified through struggle. So a tool that intends for us to never struggle is at fundamental odds with the pains that shape us and our ability to understand each other.

And on the chair analogy: we can refuse to use chairs as they are designed (or even entirely). And we can use chairs for more than sitting. And we can design new chairs and non-chairs that do any sort of thing. We have the power and the responsibility to make our technologies shape humanity into something good and meaningful.

So what do we do with AI?

Tools are immensely influential: they have the ability to mold humanity, to include and exclude, to define what matters, and to literally shape the climate and environments we live in. “Tools” are radically powerful extensions of human will.

I want to argue that AI agents (as the corporate-controlled transformer and diffusion based models of our modern day) are largely bad to use, especially now, and in most all contexts. Their dangers are environmental, economic, and existential. As a “tool” they are far too destructive.

On the environment: modern AI agents have accelerated climate change and come at an immense cost to our already precarious world. Continuing to use them is actively consenting to their ongoing destruction of our fresh water and energy resources. However, like many environmentally destructive industries, we could reign them in with policy and better, more efficient tech and infrastructure. Maybe someday the environmental damage will be under control and AI will be truly “sustainable.”

On the economics of AI: Modern multi-billion parameter AI models are scaffolded on and made possible by the largest heist in human history: theft of everything that could be scraped from every corner of the digital spaces we share. Without prevention of and justice for this damage caused by current models, their use is highly fraught, ethically. We, as human beings, have developed complex social forms of intelligence when it comes to dealing with things like credit and provenance, two things that modern models are incapable of. And without monetary and policy recognition of the entire global economy of labor that enabled current AI models, using them is active permission given to the theft of all human art and knowledge.

On our existence:

Tina He writes on our ontological crisis with modern AI, “we are awakened to the danger precisely through contact with it. The same algorithmic indifference that unsettles us may also jolt us into a higher vigilance, a refusal to hand over the entirety of our experience to optimization, market logic, or digital control. The very anxiety these systems produce is a clue: something vital, unquantifiable, and irreducibly human still resists.” He continues, “This isn’t about throwing away the tools, but about wrestling them into alignment with what we find sacred or essential.”

So that is our charge. Our job now is the same as it always as been: to fight for our own humanity and for the health of the world, to not use tools uncritically, and to shape our tools before they shape us into flat nothingness. We can turn these modern models into things that mean something to us, but we need policy, economic justice, and guardrails in place. We need to reimagine what they should be for and continue to explore and innovate ways that we can continue to create and experience meaningfully.

Go and do what machines cannot: advocate and fight for policy change, resist and refuse unjust systems, recognize by name those who taught and inspired you, “appreciate [your] predecessors and fellow-workers in the saltmines of literature,” as Le Guin remarks, and feel the good kind of pain that gives us shape and meaning; become.