Life advice to a graduating student

Advice I would have given to my past self, who was graduating college.

Obviously, my advice here is intended towards students who are graduating even though it is written towards myself. Some stuff I say here, like referencing my upbringing or my theology/philosophy degree, are not broadly applicable to other people.

But presenting this as an honest letter from myself now (about to finish a PhD) to myself 10 years ago (about to finish my undergrad) is important because many of the anxieties and the fears I had then are simply not present now. I’m also on the job market, but I’m in a completely different space (mentally, physically, socially, and materially).

Background

This blog post started from a few places. Every now and then a student of mine asks me for life advice (and I’ve never really formalized it). But often, the way I structure the advice is the same: internal, external, and specific advice related to our present-day philosophies and cultures of the “work-self” and “work-life” in the US and tech industry.

So, in order for the advice below to really make sense, I first just want to add context about myself and my past: I am diagnosed ADHD (was diagnosed in the 90s), am also neurodivergent outside of the scope of ADHD (whatever we call that isn’t too relevant to me), I have lived with a few disabilities (one of which required multiple surgeries before I turned 19, which nearly killed me), and my family life was a mess.

But my mother at the time was a drug addict on social security disability and a public school teacher’s pension (which she took early). At 18, she had kicked me out, so I was on my own. My father is homeless and completely out of the picture.

At 19, I was recovering from a major surgery. I had no job prospects and no chance at college, but I was still on my mom’s health insurance during my surgeries (because I was still technically 18). My final surgery was 5 days before I turned 19. I barely escaped in time. (Later, Obamacare extended my insurance until 26, which definitely saved my life.)

But I did odd jobs and side work for a few years. I became best friends with my now-wife at a pizza shop where she was a supervisor. And I eventually got fired from that job (the only job I’ve been fired from, mind you).

The downward spiral that sent me on, in a roundabout way, led me to college. I volunteered with youth programs, one of which was run by my upstairs neighbor (in the duplex I was in). When I was chatting with her about my woes (like, “I can’t even keep a pizza job, what am I good for?”), she suggested that I speak to the academic dean at a small liberal arts college down in Everett. They value community work and focusing on that part of myself in an application, in addition to my inclination towards philosophy, might help me get a scholarship.

I did, and it paid most of my way through my 5 years.

But graduating was hard. I had no safety net. I also had just picked up a second degree (in “computer information systems”) to try to get a tech job, since I was pretty confident at the time that a theology and philosophy degree wouldn’t cut it.

So, if I could travel back in time, this is what I’d say to a student like me, full of anxiety and fear and an unhealthy amount of self-loathing:

My advice to a soon-to-be grad

Over the years, I did a lot of stuff that worked out in the end. A bunch of stuff didn’t. But the first thing that I’m grateful for was getting my “internal” self sorted out, despite the fact this is a pretty self-centered (literally) set of things to think about.

Internal stuff (akin to the “volition” skill from disco elysium)

The important parts of having a happy life (from an internal lens) have been:

- knowing yourself and continuing to discover what that means

- knowing what you can and cannot change in your environment

- having a willingness to navigate the tension between pushing for something and letting something go

- and getting good sleep at night

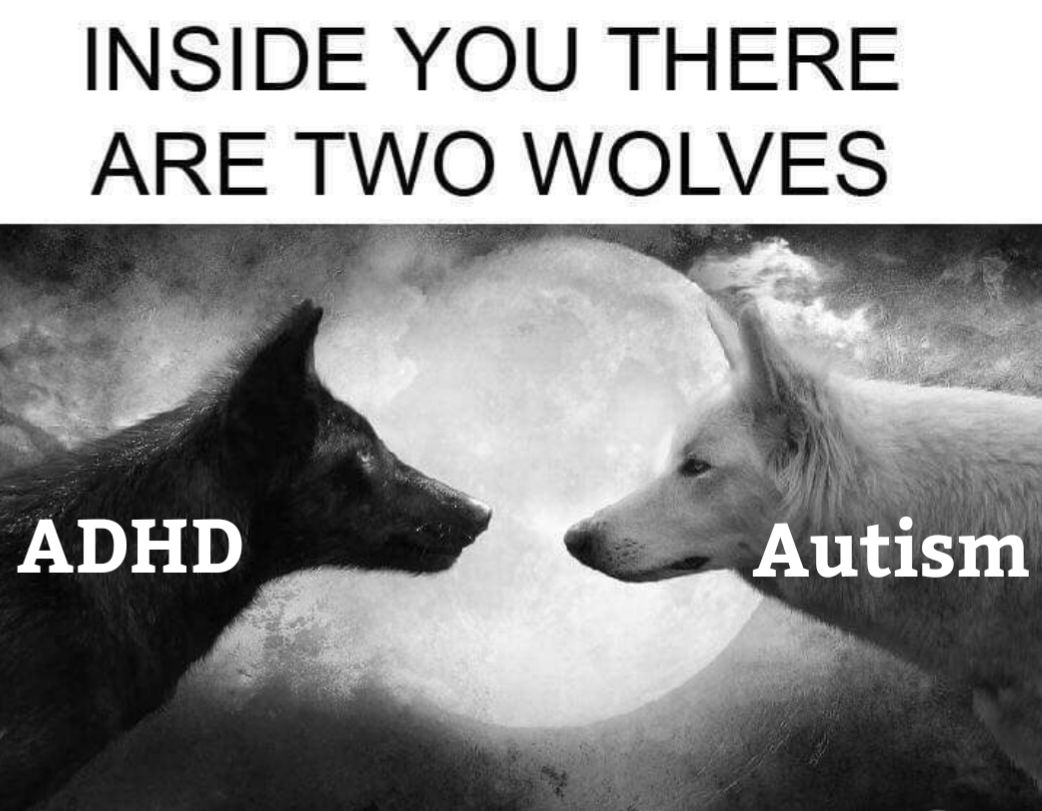

On knowing yourself, I often say that within me are two wolves: one that loves and one that hates. (These are both different shapes of my neuro-divergence.) Basically, this meme from Qasharah Reid on facebook:

Knowing that I get bored and depressed means that I need to seek stimulation. And two pure forms of motivation within me are my appreciation for the work of people who visualize data and my frustrations with the lack of access that people with disabilities have. Love and spite have carried me through so much. I’ve got that dog in me, so to speak.

On sleep: I’ve found that creating coping mechanisms and developing strategies that get me to go to bed and wake up at the exact same times every day affects my happiness, executive function, and general brain health more than any medication. It’s pretty much the number one thing to focus on, especially if you’re doing something new and hard (like looking for or getting a job).

And in the workplace (and in life, really), ADHD’ers often push far too hard or dig too deep into something at the wrong times, while abandoning or letting things go that should have been finished/wrapped up/polished. And knowing this about yourself can help you decide how to move and navigate complex landscapes like tech work. Stopping yourself and saving your energy are so key.

External/social advice

In terms of other things (outside of an internal+individualistic lens), it’s really important to also:

- DeLashmutt gave you this advice and it is 100% true, but “learn when to say no, because it allows you to say yes to other things” (and how to say no well). Your rejection dysphoria, combined with the fact you are easily distracted by new things, makes it very hard to say no to things. But people won’t hate you for having other priorities sometimes. (Do remember to say yes occasionally, though! Don’t always do everything for yourself, of course!)

- Find happiness with the people in your life and not put yourself + your work too highly in your relationships (have hobbies, friends out of work, etc)

- Do things that are socially good and gratifying (advocacy, community organizing, or volunteer work) because this will remind you that you have a place in this world that isn’t centered on a job

- Accept the kindness of others (this is especially important because you’re the sort of ADHD’er who is heavily self-deprecating, depressed, and so on). Allowing yourself to be loved is pretty much central to a life well-lived

Resisting work culture

Job-specific stuff is hard though. People kept telling me during my undergrad that, “you will be just fine, you’re going to do great” when I’d remark that I was worried about my future and how I’d find work. And I genuinely felt like I was going to crash out almost every day, but especially when someone would say that. It felt so dismissive. Do they not know that my life is barely hanging on? Do they not know that I have no safety net? My next decisions might determine whether I live or die? Whether I am miserable? Whether I ruin the lives of my favorite people, who I love dearly? There is so much at stake.

And finding a job was hard, but navigating my feelings of confusion and self-discovery during and after getting a job were even harder. I didn’t want to pick the wrong line of work! I wanted to pick the perfect job, something I was happy with. I wanted to be proud of myself for once. I also needed good health insurance (I have other disabilities, so this was really important for me). I couldn’t just do part time stuff, organizing, or live like a Bohemian creator (despite pretty much only ever wanting to write fiction).

Practically speaking, the shortform things I learned from experience were:

- Casting a wide net (applying to a lot of jobs) was good. Being open to new things was good.

- Working hard was good, but only because I learned new skills that opened up new doors (not because I was ever rewarded for hard work)

- Traveling cross-country (and willingness to move) really worked out well but it eventually burned you out. I’d pick a spot with good job prospects (and be willing to move to wherever that is), rather than bounce all around, if I could do it all again.

- In-person work is actually awesome because of people. You’ll get less work done than at home, but you can be more social, which has been good for you in life. You’ve met some of your best friends because of in-office work, despite being your happiest and most productive when you work from home. So don’t be afraid of in-office or hybrid work at first.

The deeper advice that I wish someone had given me instead of “you’ll be fine” was this:

- First, stick to your morals. You barely survived (because of luck!!) getting a job out of college that probably would have pressured you to do really terrible things. Instead, you chose work where you can look back and not have an overwhelming sense of crushing regret. You said no to projects at some of your jobs that also would have led to regret. You can stand up and say you are uncomfortable with something. And you can push back on things, too. Often times, it seemed like you were the only one to say things. But every time you did, someone thanked you (in the moment or later) about the fact that you had a backbone. Don’t let that go because you’re afraid of getting fired.

- Second, continuing that: don’t overvalue any job, ever. It’s good you pushed really hard to learn skills. Definitely put yourself in situations where you need to swim up to the surface. You thrived in those environments. But also, I’m happy because I either left places that sucked or worked to make sucky places good. So treat every single job, no matter how important it seems, as equally or less important than a waste facilities engineer or garbage collector. Software engineers might get paid more than those jobs, but that doesn’t mean that software engineers are “better” people. Those jobs are often difficult and thankless but central to a functioning society. Nobody dreams of having those jobs and nobody who has them treats their job like their whole personality. Whatever job you get, you should have the same attitude about it (it’s just a job).

- Building on that: Separate yourself from the personality of your job. You are a whole person and your work is more of a duty to yourself and society than it is some kind of mystical calling or reflection of your value. Inner value comes from you and your ability to love yourself. Outer value is often superfluous, but not meaningless, either. So seek connection with folks who know (or want to know) the whole collection of who you are, and not just people who want to judge you based on your work.

- Work less towards jobs focused on titles, positions, and identities. Simply work towards agency and material outcomes that make you happy in life. For me professionally, this is why I did a PhD: it allowed me more agency to act on my agenda (which I didn’t figure out and lock in on for several years - so it was really good that I waited to start one). Material outcomes and agency in my life right now looks like: having enough space for a gaming room with my partner, being able to take care of our dog and cat and give them a good life, having a queen-sized bed, having an espresso machine, being able to afford medical bills, working 40 hours or less every week (and mostly from home), and so on.

- On identity: Don’t try to “become” someone. Just try to do things. The depression and internalized ableism that I’ve had to overcome over the years made me recognize that wanting to “be” something was shallow. I kept wanting a title or some external measure that validated me. What you can do and what you have are far more important than who you think you “are.” And I’d even argue that seeking external validation, for it’s own sake, is destructive. It kept me, at many points in my life, from doing things. Who you are doesn’t matter, really. If you can do what is good and what you believe in and you have a good, healthy, and fun environment in your life, then you’re on the right track.

Being and becoming

This final point has been critical for me. This is ontology in philosophy. And it was queer theory that helped me understand this. And queer theory is still a really useful way to reflect on my life (in addition to other things, too). Don’t discredit your theology and philosophy degree. In many, many ways, that has been more important for your happiness than the computery one (even though you definitely needed the computery degree to land your first job and probably also to get into your PhD program).

But on identity: If you take the “ship of Theseus” problem (which is, in brief: at what point, if ever, does the ship cease to be “the ship of Theseus” as wooden boards are replaced), the problem is definitely outside of the question. “The ship of Theseus” has 2 ontologically important dimensions:

First (and this is rarely discussed) is that it is “the ship” of Theseus. The question takes for granted what it can do. It is assumed that it sails across water. It takes Theseus from one point to the next. And the unquestioned parts of our identity are often the most important ones, in this same way: be thankful for your thinking brain, your fingers, your eyes, your ability hear and to laugh, and your motivation to do things and then make them come true. Your agency, the culmination of action you are capable of, says more about who you really are than a name could.

Second (the part most people care about, which is the nominative, or unique, proper noun part of the question), it is rarely discussed, but the first questions to ask about “of Theseus” are outside of the structure of the exercise: why does it matter to even have a ship named? Does Theseus own it? If it didn’t have his name, would any outcomes for Theseus (or the world) change at all? In short, does the name afford new meaning, action, or material outcomes? Rarely, this is the case. What matters are the social and cultural forces that enable Theseus and the ship, and not the relatively small question of what the ship is called. In our own lives, our identities are the same.

In queer theory, Judith Butler in particular, helped me understand that “being” is far less useful of an ontological focus than “becoming” is. We are changing, all the time. And we are always in transition. We are performing being, which in aggregate, is becoming something of a self, of who we will be. Knowing who we are in the present is only useful if it helps us direct the trajectory of where we are going, and who we are becoming.

And in that sense, trying to gain a title or job position is almost entirely meaningless once you finally gain it. If you are climbing a mountain to reach the peak, then you have superficially invented an end to yourself. A peak is only useful as a place to rest or reflect or change course (more like a landmark than a destination).

Our being is socially constructed and we participate in that construction.

And so in the ship of Theseus question, the physical construction of the ship is irrelevant. What matters more is what the ship can do (that makes it a “ship”) and then the social assignment of the proper name, who gave it, and why. It will always remain the “ship of Theseus” so long as there is a social consensus, regardless of the wood that presently holds it together.

Anyway, you will be just fine, you’re going to do great.